Time Passages; A Painter’s Progress

Sausalito painter Gordon Studer, 66, never imagined he’d become a fine artist, wielding acrylic paints with unconventional tools on enormous wood panels. Despite being a fine arts major at Penn State, his path took several unexpected turns. Now, he’s revved up after his first solo painting show, appropriately titled “Surge” at Julie Nester gallery in Park City, Utah, where his work flew off the shelves.

“I love working big. I love how small I feel,” says Studer, who is tall. “I become a part of the painting. I get a kick out of that.”

It was a different story in the late ‘80s when he worked at the San Francisco Examiner. Back then, he was one of the few illustrators in the country skilled in using a desktop computer. Paint wasn’t his medium. He was part of the avant-garde movement of digital creators. His work appeared in major publications like TIME magazine, the New York Times, and Newsweek. Corporations like Adobe, IBM, and AT&T sought his services.

He rented a sleek Emeryville loft and dove into a promising freelance career, until it crashed during the 2008 financial crisis and the decline of print media. Unable to adapt quickly, he switched gears, building websites for clients but still found himself in debt.

Then, just before the pandemic, after doing various temporary jobs—including managing an artists’ residency in Napa—he had an epiphany. He decided to try painting again. “I watched these international artists work every day, and it hit me that I also wanted to be an artist,” he recalls. A friend in Los Angeles offered him a studio, and for a year, he painted.

“A whole universe opened up. My first big break was the de Young Museum’s Open call for artists. I had never sold a thing, but I submitted two of my paintings, and both got into the show,” Studer says. “People in San Francisco thought I was an established artist from LA who they just hadn’t heard of.”

Studer’s work also caught the eye of a manager at the Kneedler Fauchère furniture showroom, who sold it in their LA and San Francisco locations. An invitation to a group show in Calistoga followed. “It all started rolling quickly after that,” he smiles. In 2021, he found a pricey studio in the ICB building in Sausalito, and made ends meet by leading workshops there. Private commissions followed, interior designers took notice, and now galleries are knocking. “Taking risks is expensive, but I never imagined it could be this good,” says the artist. Gordonstuder.com

Get My Drift: Cathy Liu’s coastal musings

San Francisco artist and designer Cathy Liu divides her time between the Big Island of Hawaii and the mainland, where she lives with her husband, architect Craig Steely, an avid surfer. In Hawaii, she is inspired by the ebb and flow of natural forces, observing them in lava fields and at the water’s edge.

Her earliest works were painted on plywood offcuts, evolving into colorful, amoebic compositions that followed the grain of the wood. These pieces were intended to illustrate how even the smallest organisms—much like the scraps she painted on—are part of a larger whole. Paintings on canvas followed, and her work was included in San Francisco’s premier de Young Open exhibition in 2020.

Now, pieces of driftwood gathered along the California coast from Santa Cruz to Sea Ranch — some as small as 2 inches long — have become the latest ‘canvas’ for her work. “I choose the driftwood very carefully,” she says. These pieces, which wash up every day, have their own stories and also contribute to what she describes as a majestic, cosmic “whole.” After they are cured and sanded these pieces of wood are painted and given this last reverent rite in their singular journey.

Sign of the Times;

A Mission gallery turns the clock back

The House of Seiko in a former watch shop on 22nd Street, is unlike other Mission galleries that mostly feature artists working with new technology.

When they opened in 2023, curator Cole Solinger and co-owner Nicolas Torres, who also helms the hip wine bar Buddy’s two doors away, planned to exhibit contemporary art from around the globe.

However, more than 18 shows and events in, these 30-year old gallerists are drawn to Bay Area artists from as far back as the 1950s.

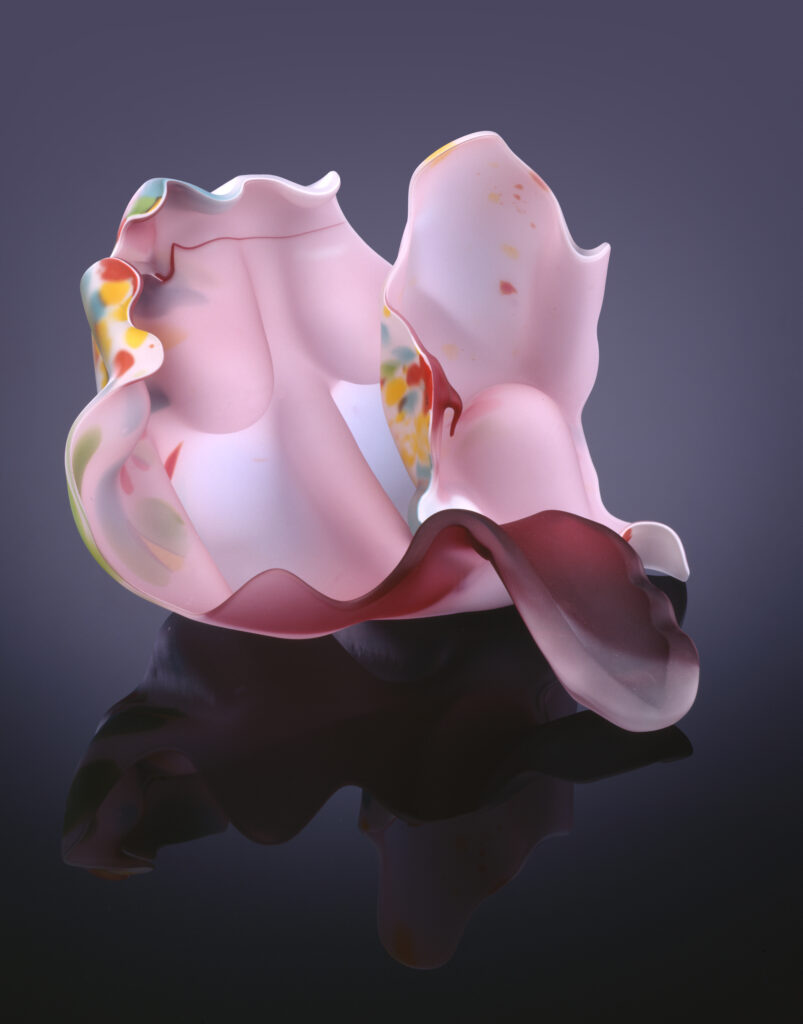

Visionary Bay Area artist Ariel Reynolds Parkinson who worked back then and died in 2017, was one of them. Her surrealist work, straddling the Beat, Rock and Hippie eras, was rediscovered by guest curator Zully Adler at the Oakland Library’s White Elephant sale, and lionized in a two-part show at House of Seiko. Solinger will again shine a light on the Bay Area with displays of glass artist Marvin Lipofsky’s bulbuous blown-glass creations from March 22 through May 4, to coincide with a major retrospective of the master at the Crocker Art Museum. By the time Lipofsky died in 2016, he was lauded as the father of the Studio Glass movement in Berkeley and Oakland. “I have become passionate about the poetics and the art movements of the Bay Area,” Solinger says. Raised in Silicon Valley, he studied print-making at the San Francisco Art Institute and simultaneously apprenticed at New Bohemia Signs, hand-painting signs. Later. while moonlighting in museums, doing preparatory work, he learned the rudiments of running a gallery where he can finally bring the area’s cultural DNA to the fore.

“San Francisco has a dense legacy of artists whose work has not been seen enough,” he says. “Even during the ’80s and ’90s, it was a hotbed of activity and that’s a lot of historic capital.” Houseofseiko.com

Machines can Draw; Seeing is Believing

Stephen Milborrow, 66, grew up in South Africa before arriving in Silicon Valley in the early ‘80s, armed with several degrees and quickly establishing himself as a telecommunications engineer. Later, he moved to Petaluma, and about 20 years ago, he felt it was time to start drawing and painting again, as he had during one phase of his education.

“I was always interested in both engineering and art,” he recalls, remembering what drew him to both disciplines when he was barely ten. “I saw a drawing of a rooster by Picasso and felt its totemic power.” In the family’s collection of Time Life books on space and a variety of other topics, he also discovered an article about a three-wheeled robotic tortoise by William Grey Walter, activated by electrical commands. “It was perhaps an early example of AI, and it was very inspiring,” Milborrow reflects. “I wanted to create something like that. It has always been a part of who I am.”

He continued to think about it. “I started painting images of robots, humans, and animals in landscapes,” he says, depicting them as sentient beings. Perhaps that helped define what he wanted to do: build a drawing machine with a ‘brain’.

“I had this idea of building a machine that could draw pen and ink portraits on paper,” Milborrow explains. Despite spending many hours on figure drawing, portraiture was never his forte, so he wanted to explore how expressive a machine-drawn portrait could be.

When the pandemic struck, he felt an urgency to complete the project he had been tinkering with for years before he became unable to write complicated code.

A year later, he had a robot that could actually observe a subject and draw in real-time. “The machine essentially comprises a computer running the coded software (the brain), a swiveling video camera (the eyes), a moveable arm to which any pen can be clipped (the hand), and a drawing surface on which the fine-toothed paper it draws on is placed,” Milborrow describes. The robot starts fresh each time and records no data.

“A computer drawing is a fairly obvious idea, but there are ideas in the code I wrote that are perhaps novel,” says the inventor modestly.

That’s why he was reluctant to call it a mere ‘artbot’ and instead named it Nonoti, after a life-sustaining river near his native Durban. The machine ‘recognizes’ the subject’s eyes and mouth and scratches out tentative positions for them. “When a sitter moves, the machine responds to changes in the subject’s pose or expression, which gives the drawing a sense of life,” Milborrow observes. The monochromatic images, produced in about 10 minutes, are expressive, scratchy likenesses that are decidedly not photographic. “The drawing takes place over time, and mistakes are made and corrected,” Milborrow says. “That history is recorded on the page, just like in an actual drawing. The struggle is visible.” It’s real.

@nonoti.machine

The Cutting Edge;

With an Xacto knife, She’s A Lacemaker

Her materials and tools are simple—paper, a pencil, and a sharp Xacto knife—but the intricate tracery of floriated patterns that artist Sara Burgess, 53, coaxes from linen-like sheets of white Japanese Kozo and Nepalese Lokta papers is a lacy marvel. What she calls “good connection points” hold the compositions together.

Though her work may evoke cutouts from ancient China, where paper was invented, Burgess’s high-key monochromatic pieces are unmistakably contemporary. They begin with a penciled pattern to guide her cutting, and the finished works are lightly mounted onto another sheet, allowing the negative and positive shapes to cast subtle shadows onto the backing, adding relief.

Art and craftsmanship are woven into Burgess’s upbringing. Both her parents were ceramicists in Manchester, England, where Burgess was born, and later, on their sheep farm in North Wales. When she was ten, they moved to a remote area of Vancouver Island in Canada, where they built another studio kiln by hand. Along the way, Burgess’s mother, a back-to-the-land advocate and expert seamstress, taught her to sew and embroider—skills that influenced some of the motifs Burgess now incorporates into her cutouts. They are the fiddlehead ferns, Queen Anne’s lace, nettles, brambles, and flowers of her rural childhood.

It wasn’t until she arrived in San Francisco to pursue a master’s in illustration at the Academy of Art University that she could fully explore her artistic roots. After college, she interned at Hallmark Cards in Missouri and later returned to the Bay Area as a ceramic tableware designer for Pottery Barn before moving to a hilltop home high above Mill Valley in 2011. There, she set up a vintage press for linocut printmaking, another of her passions. The cut paper process began by accident when she realized the sketchbooks of drawings for linocuts piling up had many unused pages. “I started cutting patterns directly into the pages of the books,” she says. “I liked the positive and negative shapes, and soon I pulled out pages for cutouts.”

Recently, in a small studio in Sausalito, she has been experimenting with paper shapes hand-stitched together to form abstract, flower- or plant-inspired collages. “I perforate the paper and then stitch it,” Burgess explains. The dark-thread stitching forms lacy patterns. “I enjoy the outcome and the variation,” she adds. “The change of pace helps to rest the body,” Burgess says, reminding us that her delicate cutouts, are very hard work. Saraburgessstudio.com

Casting Call;

In Berkeley, one last great foundry

One morning, San Francisco artist Paul Lanier led the way into the Artworks Foundry, a hidden gem in the East Bay that he holds dear. Not far from Berkeley Bowl West, the foundry is nestled within a sprawling compound of manufactories and artist studios, collectively known as the Berkeley Art Complex. It’s surrounded by open-air lots filled with foam and plaster maquettes of towering sculptures. These unintentional neighbors—giant heads, soaring angels, equestrian monuments, and abstract constructions—together form a surreal, almost deserted landscape.

Founded in 1976 as a small bronze casting and manufacturing business by Italian craftsman Piero Mussi, trained in ancient metallurgic arts and lost-wax techniques, the foundry soon attracted renowned artists like Stephen de Staebler, Mildred Howard, Peter Voulkos, Nathan Oliveira, and Lanier’s mother, the educator and sculptor Ruth Asawa.

Half a century later, it remains one of the last and largest of its kind in California. Since 2019, the foundry has been led by its current owner, Kambiz Mehrafshani, a 45-year-old Bay Area native who was once a customer and fell in love with the craft. He introduced changes while preserving the spirit of this treasured resource. Spanning over 25,000 square feet and anchored by a World War II-era water tower that Mussi converted into his home, the foundry now boasts cutting-edge technologies like 3D printing, CNC machining, and other forms of digital manufacturing. “Maquettes can be scaled up faster to full-size sculptures with the click of a mouse,” Mehrafshani says, pointing to the ever-increasing demand for monumental work, which may require bigger and more efficient facilities in the future.

More than 2,000 active artists rely on the foundry’s expertise, with 25 specialists—some of whom are artists themselves—crafting new bronzes and restoring old reliefs and monuments from around the world. It’s a hive of activity. Inside nearly every structure that contains kilns, crucibles and workshops, casts are being made, large works are being welded together with blowtorches, and completed sculptures are being prepared for their final patinas before showtime.

“At the end of each day, our hands are dirty and our ears are ringing from the sounds of metal,” Mehrafshani says. “But this work is life-giving.” Artworksfoundry.com

House Proud;

A fashion maven turns to furnishings

Berkeley clothing designer Erica Tanov has literally found a home for her dormant passion: interior design. Inside a refurbished 1870s Italianate Victorian mansion she calls the Erica Tanov Atelier, the designer has arranged furniture finds from estate sales alongside her Yves bench, inspired by vintage furniture. “I love to mix design styles,” explains Tanov, and so its spare silhouette with turned wood legs is both Modern and Classical at the same time, and covered in contemporary printed canvas of her own design. Sourced linen, velvet and mohair fabrics are optional. Tanov’s recently-launched three-story atelier, where selected finds and the Yves line are displayed artfully against bare plaster walls, echoes the sophisticated earth-toned aesthetic of her long-time fashion boutique, which is only paces away from the mansion.

The Atelier also serves as a salon. Tanov sometimes plays ‘hostess’, by appointment, for groups and events such as San Francisco Design Week amid the ever-changing inventory of furnishings — and fashion is ever present. Silken robes and some garments, hand-embroidered or appliquéd in India with centuries-old motifs, are shown alongside 19th century Spanish Revival furniture, mid-century modern objets and handcrafted one-of-a-kind sculpture. The tableaus of repurposed objects as well as revived crafts and patterns for her lines of wallpaper, curtains, linens, and bath tiles (made by Clé) are just different avenues of glamorous self-expression for the fashion designer. In such an inspiring setting, Tanov and her ‘guests’ can slow down, take the weight off their feet and sit down for a conversation. The table is always set with beautiful things, and the bed is always made.

Clearly, Tanov resists modern technologies and materials, so although the made-to-order furniture ranging from $1240-$8600 can be ordered in an instant online, it will take several weeks to arrive. Even in a sped-up tech age, Slow Design is worth the wait? Ericatanov.com

On City Streets;

Just three words will get you art

You won’t find Ben Bernthal, a 36-year-old conceptual artist and founder of Strangers’ Poems, careening down hillsides like characters in the iconic TV series, “The Streets of San Francisco.” Instead, you’ll see him drawing and writing poetry in the flattest parts of town such as the Mission, the Ferry Plaza and Fort Mason. There, next to his ‘poetry table’ on wheels, he asks customers a few questions about themselves and then leads them into a ritual or “divination” that sometimes involves hammering a nail into a closed book. Participants choose from among the words the nail strikes and Bernthal, tapping away on a vintage typewriter, incorporates them into a poem. Sometimes he types on illustrated sheets that can be framed as broadsides. “People are visibly moved by it all,” he says.

His “artifact sessions” at the Legion of Honor while he was an artist in residence at the Fine Arts Museums during National Poetry Month in 2024, were popular. One performance took place in front of a mummified Ibis from Ancient Egypt, where he conjured up descriptive, ekphrasis poems that referenced Thoth, the god of writing, who Egyptians depicted as the now critically endangered bird.

At a Google Cloud company event, Bernthal co-created postcards with participating guests that anyone at the event could read. “It was gmail using analog rather than new technology,” he explains. “Even if it is not poetry in form it feels poetic in essence.”

Born to a Lutheran music theory professor and pipe organist, Bernthal left Valparaiso, Indiana in 2016 to teach English in Japan. He later followed a girlfriend to Nashville, North Carolina where he first began his street gigs.

“I had gone to school for audio engineering and fell in love with poetry,” he says. Inspired by artist Laurie Anderson, he realized that all he needed was himself, a few objects and the street. “I made my own path,” he says.

He continued performing worldwide until, by serendipity, he landed at his apartment in a subdivided 1908 synagogue in the Mission. An artists’ haven since the mid-1900s, it was once home to the renowned 1980s sculptor, Frida Koblick. Its current landlord, Dan Friedlander, a former influential curator, introduced avant garde furniture (in spirit, akin to Koblick’s cast acrylic sculptures) at his now-defunct Limn Furniture store in San Francisco. Some of Friedlander’s pieces, including a winged Birdie chandelier by Ingo Maurer, linger in the apartment, which Bernthal shares with a fellow artist.

The repurposed loft-like building retains many original details, including windows with Star of David motifs. Large skylights flood light into what was likely once part of the congregation hall, giving Bernthal an alternative salon when the weather turns.

This space allows him to act as a micro-publisher, creating limited edition poetry broadsides. “Setting up an installation inside rather than on a street corner, guerrilla style, is ok,” he says. @Bbernthal

Empowering graphics

Making a difference with art

An unlikely arts enclave exists within a gated storage ‘park’ not far from the Richmond ferry terminal in the East Bay. Opened in 1993 as Bridge Storage, with hundreds of storage units and shipping containers, it gradually evolved to include art-making and gallery spaces after Jeff Wright, the son of the founder, repurposed several storage units into affordable, climate-controlled art studios. Now known as Bridge Storage & ArtSpace (with BridgeMakerARTS as its latest non-profit offshoot), it is also a vibrant gathering spot, offering shared workshop and gallery spaces for creators of music, art and graphics.

Among the younger artists at Bridge is Eli Utne, 34, son of the founders of The Utne Reader, an influential counterculture print journal that explored topics like the environment, spirituality, technology, and the arts. In the same spirit, Utne is a musician, artist, teacher, and eco-conscious land management enthusiast all rolled into one. He has been based at Bridge for nearly seven years, working out of a 100-square-foot pre-fabricated shed that he’s decorated with murals and outfitted with recording equipment. True to the times, he draws on his iPad, records music on his phone, and mixes it on his computer.

“I am a social artist,” he says. “In my career as an artist and educator, I’m focused on performing, songwriting, composition, and recording.” He performs across the country — including a music pop-up at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis — teaches guitar, sings in an avant-garde Oakland choir, and has released two vinyl albums of his own music.

He has also founded Learning by Hand, an esoteric company that offers practical, hands-on education through small workshops teaching people how to be self-sufficient — for example, by learning to draw, screen print, make ceramics, and craft other useful everyday objects. “The Bay Area has different threads of history and culture that converge here,” Utne says. “These are just ways of linking that world.” Learningbyhand.org @learningbyhand

At Bridge, there are others who blend art with technology. Just a few doors down from Eli Utne’s studio is the bustling workshop of David Solnit, the 61-year-old co-founder of the influential 20th-century counterculture movement, Art and Revolution. A carpenter, puppeteer, graphic artist, and community organizer, Solnit works out of a large pre-fab structure where volunteers and clients help screen-print political protest posters and banners expressing everything from worker solidarity to concerns about climate change. Solnit has co-authored three books on these topics, including one with his sister, the renowned feminist/activist author Rebecca Solnit. It’s no surprise their mother also organized neighborhood groups in Marin.

The often visually arresting artifacts produced in Solnit’s shop are frequently designed by him on a computer or directly cut onto Rubylith stencils, then turned into silk screens for printing. These works represent some of the Bay Area’s most impactful messaging, partly because their graphics are legible from afar. One timely collage, created digitally just after the Pacific Palisades fire, isn’t a protest piece but an ode to Los Angeles. “I always wanted to be an artist but didn’t know how it could contribute to social change. Then I realized public action is a form of art,” he said. @davidsolnit