For Tucker Nichols, 55, who was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at an early age, art became a vital way to express what words often fail to capture — even chaos. Raised in Boston and now based in Marin County, Nichols realized early on that working in bursts, between bouts of illness, was the only viable path forward. Being an artist, he decided, was one possibility.

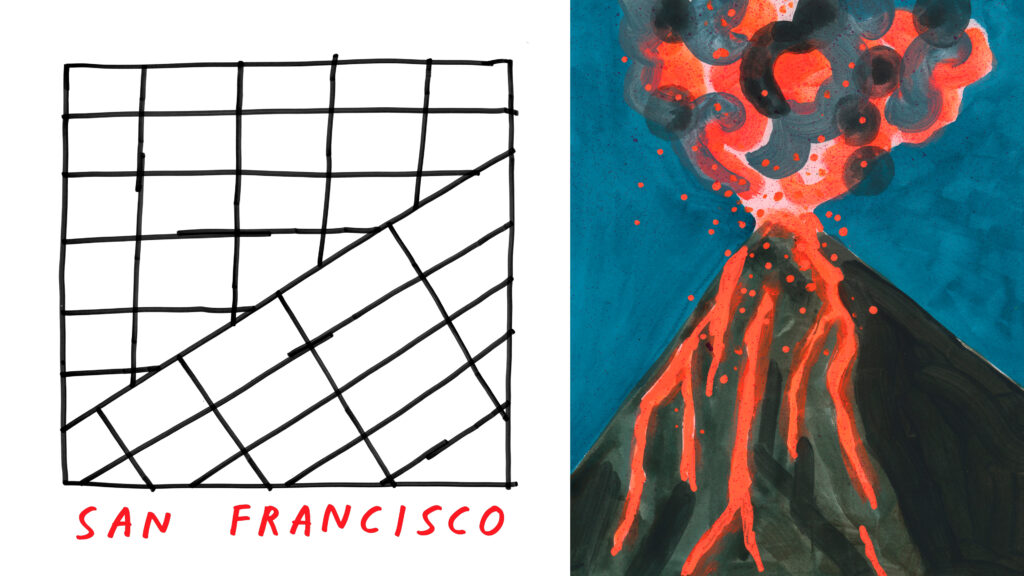

While earning a master’s degree in the history of Chinese painting, Nichols began taking short walks, sometimes on the beach, to regroup — observing nature, collecting objects, and quietly recharging. That habit never stopped. A rock shard shaped like California? Keep. A battered piece of driftwood that resembles a duck? Also keep.

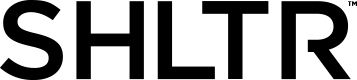

On days he stays indoors, Nichols draws and paints what he’s thinking or feeling, turning thoughts into visual codes. This work — often cryptic, occasionally comedic — has appeared in The New Yorker and the New York Times Op-Ed pages. One sketch for an article on tax evasion simply reads: “$$$HH.”

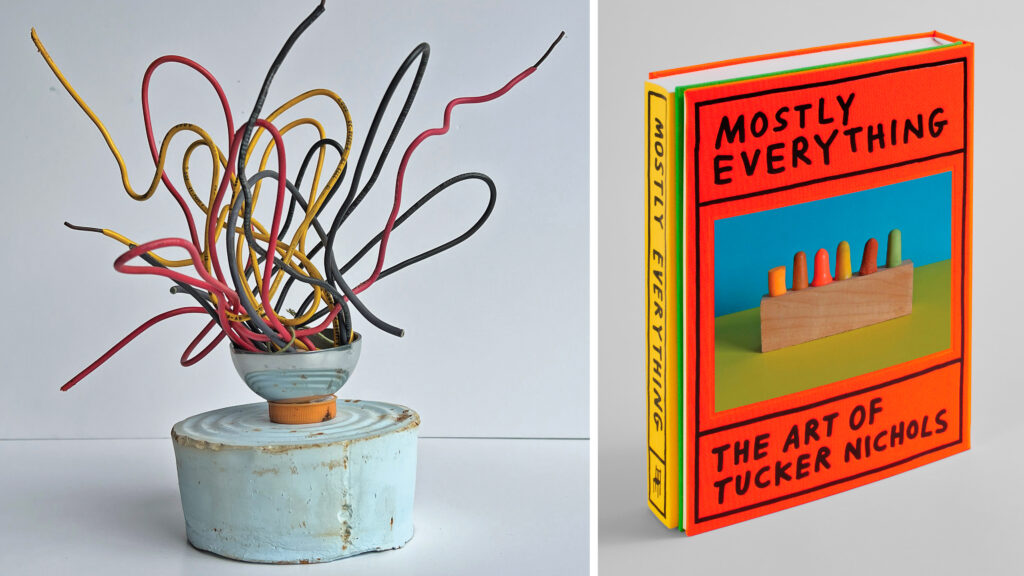

Nichols’ practice blends sardonic humor with a tender sense of wonder. His output — drawings, wordless cartoons, collages of found objects, diagrams, flowers, people, places, and things — has long appeared piecemeal: in books, exhibitions, T-shirts, tote bags, and sprawling installations. Now, it’s all collected for the first time in a bold, genre-defying volume.

Titled Mostly Everything: The Art of Tucker Nichols, and designed by Sunra Thompson, the book is published by McSweeney’s in San Francisco. It’s a neon-red, double-spined, hard-to-categorize monograph. Or as Nichols describes it, “an exciting object.” There are no explanatory essays — only his drawings and diagrams, eloquent and strange, layered with meaning.

We spoke with Nichols about the book’s many chapters — Humans, Landscapes, Diagrams (the wordiest), Flora, Sculptures, Monuments, Science & Technology,and Creatures — but Flora, admittedly, always seems to rise to the top.

His connection to flowers runs deep. Nichols’ mother was a competitive florist, and he was often her assistant — especially at the Philadelphia Flower Show. “Growing up, my brother and I couldn’t use the kitchen sink because her cut flowers were stored in there,” he recalls. She was always rearranging their home with odd flea market finds and floral arrangements. Through her, he absorbed a natural fluency in spacing, absurdity, and composition.

Flowers, for Nichols, are more than subjects. They’re a medium for emotion. “You can say almost anything with a flower,” he says. “The boundary between abstraction and representation is solved with flowers. The same flower can mean different things. We use flowers because we don’t know how to put something in words.”

That insight reflects the emotional core of his work. While many of his drawings may appear abstract, they are almost always rooted in real-world references — like a crosshatched watercolor of a forest after a fire.

“If I paint something abstract with no reference to the real world, it has no reason to be,” Nichols says. “For me, flowers have just enough content. They can be abstract, but they’re also these little packets of emotion being captured. ” tuckernichols.com, mcsweeneys.net